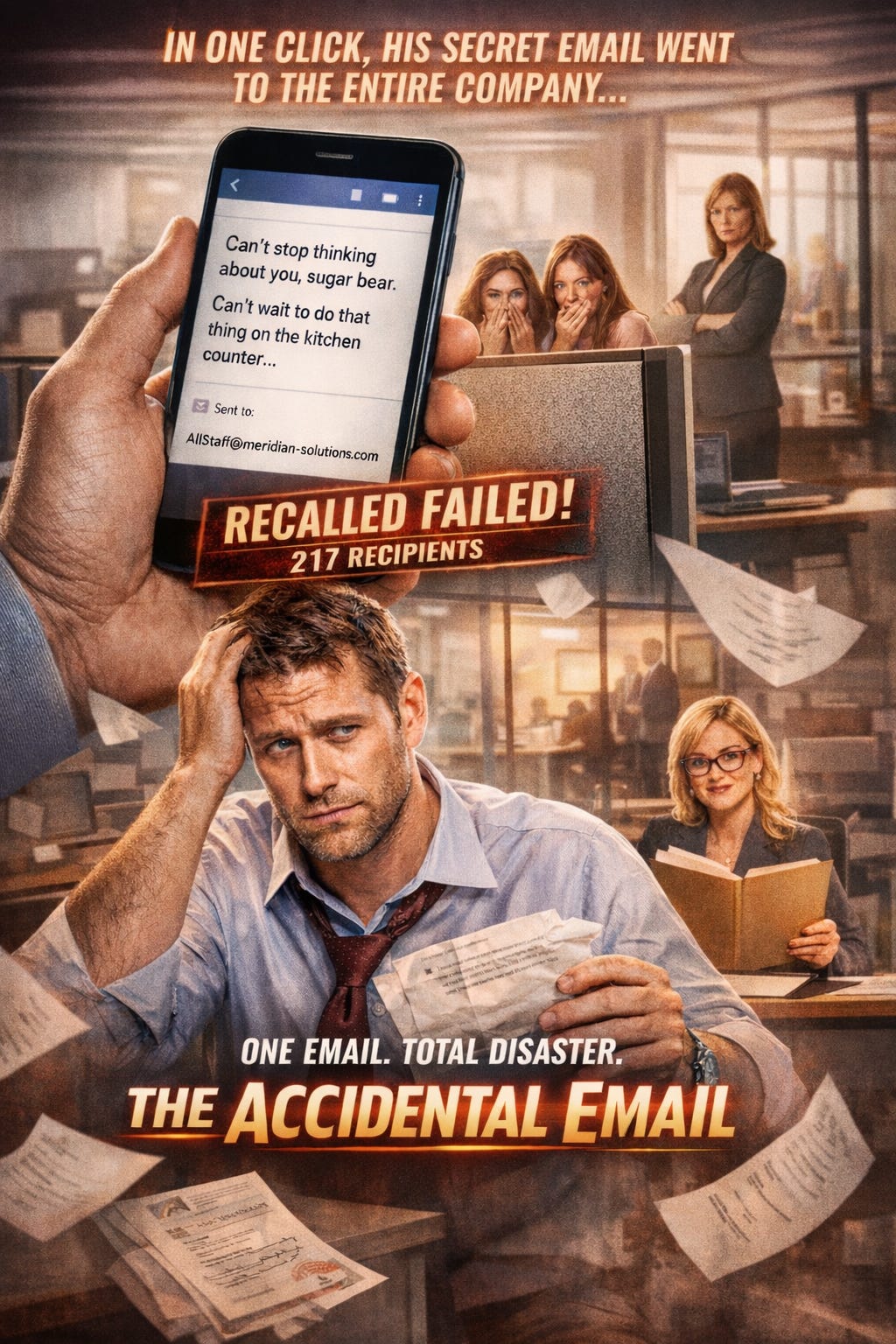

The Accidental Email

The morning had been going fine. That was the thing Dave would keep coming back to — the sheer, unremarkable fineness of it. Coffee from the pod machine. A granola bar from the vending machine. An email from Lisa about Saturday night, which he’d opened while half-listening to a conference call about Q3 retention metrics.

He’d typed his reply with one hand, smiling at his phone with the other, because Lisa had used the voice-to-text thing again and autocorrect had turned ‘casserole’ into something that was not casserole. He’d written back in kind. Leaned into it. Added a few lines of his own that were — in the context of a private marriage between two consenting adults — perfectly normal and even, he thought, kind of sweet.

Then he’d hit send and gone back to the conference call, and for four entire minutes, Dave had continued to exist in the version of reality where that message had gone to his wife.

The first sign was the silence. Not the absence of noise — the open-plan office at Meridian Solutions was never quiet — but a new texture to it. Fingers stopped on keyboards. A laugh, bitten off. Someone across the floor said ‘oh my God’ in the specific register that meant they weren’t talking to God.

Dave looked at his sent folder. He looked at the TO field. He looked at it for a long time, the way you’d look at a spot on an X-ray.

The conference call distribution list. The entire conference call distribution list. Every person on the Q3 retention metrics chain — which, because someone in Operations had added the whole department last quarter and nobody had ever cleaned it up, meant everyone. Not just his team. Not just his floor. Everyone who had an @meridian-solutions.com email address and a pulse.

Dave clicked ‘Recall Message.’ The system thought about it. Then, with the gentle indifference of a machine that does not understand human suffering, Outlook informed him that message recall had failed for 217 of 217 recipients.

His face did something complicated. Then his hand found the phone on his desk and he was dialing Lisa, watching his fingers move like they belonged to someone else, someone whose life was actively collapsing. It rang four times and went to voicemail. Right. School drop-off. She’d have her phone in her purse, volume down, singing along to whatever the kids wanted on the radio.

A head appeared over the cubicle wall. Marco, already biting his fist.

“Bro.”

“Don’t.”

“Dave. Davey. My man. Did you just send the entire company —”

“I know what I sent, Marco.”

Marco opened his mouth. Closed it. Opened it again. He looked like a man trying to choose between seventeen different jokes and finding each one more beautiful than the last.

“Sugar bear.”

Dave’s stomach dropped through the floor. Because there it was — one specific fragment of what he’d written, said back to him in Marco’s voice, in the fluorescent light of a Tuesday morning, and it sounded nothing like what it had sounded like when Lisa first called him that in bed three years ago. It sounded like a thing that would follow him to his grave.

“You need to stop talking.”

“I’m helping. I’m on your side. I just need you to know — and I say this with love — that Brenda in Accounting is crying. Not sad crying. The other kind.”

Dave’s computer chimed. New email. The sender was Janet Okafor, his boss, and the subject line was empty. The body of the message was three words long: My office. Now.

He stood up. From three cubicles away, someone started a slow clap. It was picked up briefly by a second person before dying out in a muffled snort. Dave walked toward Janet’s office with the careful posture of a man approaching a gallows, and all he could think — the only thought his brain would produce, on a loop, crowding out everything else — was that Lisa still didn’t know.

***

Janet’s office had glass walls. Dave had never thought about this before, the same way you never think about the walls of an aquarium until you’re the fish. He could feel the floor watching him cross the last ten feet — not staring, exactly, but orienting, the way a field of sunflowers tracks the sun. He was the sun now. The worst possible sun.

Janet was behind her desk, reading something on her monitor. She didn’t look up when he came in. He closed the door behind him and stood there, waiting, while she finished whatever she was reading. He had a pretty good guess what it was.

She gestured at the chair across from her. He sat. The seat put him about three inches lower than her, so he had to look up slightly, like a kid called to the principal’s office. Janet still hadn’t spoken.

“Dave.”

“Janet.”

She turned her monitor so he could see it. His own email, right there on her screen, the preview pane showing enough of the text that he could read the words ‘can’t stop thinking about’ and ‘sugar bear’ and — oh God, the part about the kitchen counter. He looked away.

“You tried to recall it.”

“I did.”

“So now everyone who deleted it unread has a notification with your name on it telling them to go find it.”

Dave’s mouth opened. Nothing came out. His hands found each other in his lap and held on.

“I have Pinnacle Foods in this building at two o’clock. That is the single largest account renewal on my desk this quarter. I need my team focused. I need this floor functioning like a workplace and not a group chat. Tell me you understand that.”

“I understand that.”

“What I don’t need is the origin story. I don’t need to know about the autocorrect, or the voice-to-text, or whatever happened with the distribution list. I need to know what you’re going to do for the next six hours to make this not be the only thing anyone’s talking about when my clients walk through that door.”

Dave opened his mouth to answer and his phone buzzed in his pocket. His whole body flinched. Lisa.

“Don’t.”

He left it.

“Here’s what’s going to happen. You’re going to go back to your desk. You’re going to do your job. You are not going to send a follow-up email, you are not going to reply to anyone who replies to you about this, and you are absolutely not going to try to recall anything else. Are we clear?”

“Crystal.”

“HR is going to want to talk to you. That’s not my call. That’s just how this works when something like this hits a company-wide list. I told Karen I’d send you over after we spoke.”

Dave felt something cold settle in his chest. HR. This wasn’t just embarrassment anymore. This was a file. A record. A thing with his name on it that would outlast the jokes.

“Janet, it was an accident. I was replying to my wife and I —”

“I know.”

That was worse. The gentleness was worse. He could have handled anger. He could have handled a lecture. But Janet looking at him like he was a weather event she needed to route around — that was the thing that made his ears burn.

“Go see Karen. Then come back and do your job. And Dave —”

He was halfway out of the chair.

“The Pinnacle deck. I still need your section by noon.”

He nodded. He stood. He walked out of the glass office and back into the open floor, where every pair of eyes found somewhere else to look about half a second too late. His phone buzzed again in his pocket. He pulled it out and glanced down. Not Lisa. Marco, via text: ‘bro karen from HR just walked past my desk asking where you sit. she had a FOLDER.’ Dave put the phone away and started walking toward HR, and the phrase ‘kitchen counter’ pulsed behind his eyes like a migraine.

***

Dave made it eleven steps from Janet’s office before he stopped. The hallway stretched ahead of him toward HR, and beyond that the open floor, and beyond that every person he’d ever nodded to in a break room now in possession of his innermost thoughts about his wife and a kitchen counter. But first — Lisa.

He ducked into the stairwell. Nobody used the stairs at Meridian Solutions. That was their entire appeal. He leaned against the cinderblock wall, pulled out his phone, and opened his messages.

Two missed calls from Lisa, both during the meeting with Janet. No voicemail. Probably just calling back after seeing his missed call — she’d have been buckling the kids in, seen his name, tried him twice, moved on. Normal wife behavior. Nothing to indicate catastrophe. He clung to this interpretation the way a man clings to a piece of driftwood.

He started typing.

‘Hey so something happened at work’

He stared at it. Deleted it. Too ominous. She’d think he got fired. He tried again.

‘Don’t freak out but’

No. The three worst words in the English language. Delete.

‘Remember that email you sent me this morning? The casserole one?’

Christ. He couldn’t even get past the setup. Every version required a second text that said ‘well the entire company read my response’ and there was no font size small enough to make that sentence okay.

He sent four texts in rapid succession:

‘Hey call me when you can’

‘Actually don’t call me I’ll call you’

‘Actually I can’t call I’m about to be in HR’

‘I love you and I’m sorry and please don’t check your email’

He watched the messages deliver. No read receipt. No typing bubble. Lisa’s phone was probably still in her purse, which meant he had anywhere from five minutes to an hour before she saw them, and in that window someone else could get to her first. Any one of the people on that list might know Lisa — Meridian Solutions wasn’t that big a company, and Lisa had come to the holiday party last year, and she’d met people, she’d been charming, she’d —

His phone rang. He nearly threw it. But the screen said LISA and his thumb was already moving.

“Hey. Hi. Don’t —”

Lisa’s voice was flat. Not angry-flat. The other kind — quiet and careful, like she was reading the serial number off a piece of equipment.

“Who is Megan Driscoll?”

“She’s in your Procurement department. We talked for twenty minutes at your Christmas party about sourdough starters. She just sent me a screenshot, Dave.”

Dave closed his eyes. The stairwell hummed with the building’s ventilation system, a low mechanical drone that suddenly sounded like the inside of his own skull.

She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t need to.

“Lisa, I was replying to you. The autocorrect thing, the casserole — I was just playing along, and I hit the wrong —”

A pause. He could hear the engine running. She was still in the minivan, staring straight ahead at the school building their kids had just walked into.

“I tried to recall it. The recall didn’t —”

It wasn’t a question. Lisa didn’t ask questions when she already had the evidence.

Dave pressed the phone harder against his ear and said nothing for a long moment. From beyond the stairwell door, he heard footsteps and a bark of laughter that cut off abruptly — someone being shushed, or someone remembering where they were.

“I’m about to go into an HR meeting. They have a folder.”

Another silence. The engine idled.

“I have to go. I can’t do this in a parking lot. I need to — I have to think about what I’m going to say to Megan Driscoll, who I now have to see at every school function for the next six years.”

“Lisa —”

She hung up. Dave stood in the stairwell holding the dead phone to his ear.

The stairwell door opened. A man from the third floor — Terrence, maybe, or Terence, Dave had never been sure of the spelling — stepped through with a coffee in each hand. He saw Dave and his whole face rearranged itself into delight.

“Hey, sugar bear.”

Dave pocketed his phone and pushed past him through the door, back into the hallway, where the lights were too bright and Karen’s office was forty feet away and he could already see the folder on her desk through the glass.

***

Every office at Meridian Solutions was made of glass. Dave had never questioned this before today, the same way you don’t question the walls of a shower until someone’s filming you. He was three for three now. Janet’s fishbowl, the stairwell’s brief mercy, and now Karen’s corner unit on the second floor, where anyone walking to the kitchen could watch a man’s dignity get entered into the permanent record.

Karen was already seated when he arrived. The folder was centered on her desk like a place setting. It was manila, thin but present, and the tab at the top had been labeled in neat handwriting he couldn’t read from the doorway. She looked up and smiled. It was a warm smile. A generous smile. The kind of smile you’d want greeting you at a bed-and-breakfast, not at a disciplinary intake.

“Dave. Come in, please. Close the door.”

He closed the door. He sat in the chair across from her. It was lower than hers. Of course it was. Every chair in this building existed to make Dave look up at a woman who had read his email.

“How are you doing?”

Dave stared at her.

“Right. Let’s just get into it.”

She opened the folder. Inside was a printout. His email, rendered in black and white, with sections highlighted in yellow. Someone had highlighted his email. Someone had taken a highlighter — a physical, analog highlighter — and drawn it across the words he’d typed with one hand while eating a granola bar, and decided which parts merited emphasis. Dave could see the yellow strips from across the desk. There were several.

“So. I want to be clear that this isn’t disciplinary. This is documentation. Any time a personal communication goes out on a company-wide distribution list and the content is of a — let me find the language —”

She looked down at a second sheet of paper. The smile held.

“— ‘sexually suggestive or intimate nature,’ we’re required to create a file. It’s not a judgment. It’s a process.”

“A process.”

“I need to confirm a few things with you, and then we’ll both sign a form and you can get back to your day. Okay?”

“Okay.”

“First — can you confirm that the email sent at 9:07 a.m. from your account was authored by you and was not the result of unauthorized access?”

“It was me.”

“And the intended recipient was your wife. Lisa.”

“Yes.”

“And the content accurately reflects your — let me just —”

She glanced down at the highlighted printout.

“— your intentions regarding the evening of Saturday the fourteenth?”

Dave’s jaw tightened. Karen’s smile had not moved. It sat on her face with the structural permanence of architecture — less an expression than a load-bearing wall.

“I don’t know how to answer that.”

“A yes or no is fine.”

“Yes. Fine. Yes.”

Karen made a small check mark on her form. Then another. She was working through a list. Dave could see at least six more unchecked boxes below her pen.

“Now, I do need to ask — and again, this is just the form — were any of the individuals on the distribution list intended to receive this content?”

“No. God, no.”

“Were any of the acts described in the email intended to involve anyone other than your wife?”

Dave felt something behind his eyes that might have been an aneurysm.

“Karen. It’s about dinner plans. It started as dinner plans. The whole thing is a — it’s a joke between me and my wife about a word her phone autocorrected, and I just — I leaned into it, and —”

“I understand. But the form asks, so I have to ask. Yes or no?”

“No.”

Check mark.

“Last section. Have you received any responses to the email that you would characterize as harassing, threatening, or retaliatory in nature?”

Dave thought about Marco. He thought about the slow clap. He thought about Terrence in the stairwell, grinning with a coffee in each hand, calling him sugar bear like they were old friends.

“No. Just... people being people.”

“Because if anyone is creating a hostile environment for you as a result of this, that’s something we take very seriously.”

The smile widened. Dave realized she meant it. She was genuinely offering to protect him — to open a second file, a retaliatory-harassment file, on his behalf. He could walk out of here as both the subject and the victim. Two folders. An ecosystem.

“No one’s harassing me. It’s fine.”

“If that changes, my door is always open.”

It was glass. He could see through it right now. He could see Terrence from the third floor standing just outside, pretending to read a fire safety poster he had clearly never looked at before, holding his two coffees with the patient focus of a man waiting for a show.

“I just need your signature here, and here, and your initials here where it says you’ve reviewed the company communication policy.”

She slid the form across. Dave signed it. His hand was steady, which felt like a small victory. He initialed the box next to a paragraph he did not read, because reading it would mean knowing exactly which clause of the Meridian Solutions employee handbook he’d violated by telling his wife she made him crazy in a way that ‘the thing you did with the —’ and then a phrase he could not look at again, not here, not with Karen’s smile three feet away.

“Great. That’s us. You’re all set.”

Dave stood. Karen stood. She extended her hand and he shook it, because apparently that was how this worked — you shook hands with the woman who’d just filed your sex life under ‘Incident Reports, Q3.’

He opened the door and stepped into the hallway and Terrence was right there, no longer pretending to read the poster, holding out one of the coffees like an offering.

“Dave! My man. Brought you a coffee. Figured you could use one after —”

“Thanks, Terrence.”

“No but seriously though, are you good? Because I just want you to know, nobody’s judging. If anything, people are impressed. Like, the part where you —”

“Please don’t finish that sentence.”

“I’m just saying. Your wife’s a lucky woman. That’s all. That’s the takeaway.”

Dave took the coffee because refusing it would extend the conversation. It was lukewarm. Terrence clapped him on the shoulder with the free hand and walked off down the hallway, and Dave stood there holding a coffee he hadn’t asked for from a man he barely knew, who now knew things about him that most of his close friends didn’t.

His phone buzzed. He looked down expecting Marco, expecting Lisa, expecting the next wave of whatever this day had planned for him. It was a calendar reminder: ‘Pinnacle deck — Dave’s section — due 12:00 PM.’ Two hours away. He hadn’t touched it. He’d been too busy having his marriage notarized by HR to do the one thing Janet had actually asked him to do.

He started walking back toward his desk, and from somewhere on the floor behind him he heard laughter — not at him, maybe, or maybe at him, there was no way to know anymore — and the coffee was lukewarm and his phone was buzzing again and he still had a presentation to write for a client who would be in this building in four hours, sitting in a conference room with people who had read every word of what Dave wanted to do on Saturday night.

***

Dave walked back to his desk. He didn’t look at anyone and no one looked at him and this mutual fiction carried him across the open floor in about fifteen seconds.

His cubicle was as he’d left it — monitor on, screensaver cycling, the granola bar wrapper still on the desk next to a coffee ring he’d made in a previous life. Marco’s head was not visible over the partition. This was either a kindness or a trap.

Dave sat down, opened the Pinnacle Foods file, and stared at a slide titled ‘Projected Churn Reduction by Segment.’ The cursor blinked. He started typing. ‘Based on Q2 retention data, we project a 14% improvement in renewal rates across Tier 1 accounts, driven by—’ He stopped. Deleted ‘driven by.’ Typed ‘attributable to.’ Deleted that. Typed ‘driven by’ again. This was fine. This was just words about numbers. He could do words about numbers.

Three slides in, the rhythm started to hold. The deck had a structure — market analysis, client history, renewal projections, risk mitigation — and the structure was a kind of mercy. Each bullet point was a sentence that had nothing to do with his wife or his body or what he’d wanted to do on a kitchen counter. He built a bar chart. He color-coded the segments. He adjusted the axis labels so the percentages were legible at projection size. It was the most careful work he’d done in months, because careful work was the only thing between him and the hallway.

“I’m a ghost. You can’t see me. But you should know that someone started a Slack channel called ‘saturday-night-plans’ and it already has forty-three members.”

Dave did not respond. He adjusted a pie chart margin by two pixels.

“Also Diane from Legal subscribed to the retention metrics list. She was never on it. She subscribed today. To read the archives.”

“Marco. Ghost.”

Silence from the other side of the partition. Dave pulled up the risk mitigation slide and typed: ‘Key risks to renewal include competitive pricing pressure from Harvest Table brands and potential distribution conflicts in the Northeast corridor.’ Normal words. Professional words. Words that had never been within fifty feet of the phrase ‘you make me crazy.’

He was formatting the executive summary when he saw movement in his peripheral vision. Terrence, rounding the corner of the cubicle row, this time without coffee but carrying a whiteboard marker and wearing the expression of a man arriving at his own surprise party.

“Dave! Quick question. Totally unrelated. Do you know if the third-floor kitchen whiteboard is, like, moderated? Because someone wrote something on there that I feel like you’d want to know about.”

“I don’t want to know about it.”

“It’s about the thing you said about Lisa’s neck. The part where you said you wanted to— “

“Terrence.”

There it was. A new fragment, loose in the building. Not sugar bear, not the counter — something else, something he’d typed fast and hadn’t reread, about Lisa’s neck and the way she tilted her head back when she laughed, and what he wanted to do about it, and now that sentence was on a whiteboard next to the coffee machine on a floor he didn’t even work on. Dave’s hands stayed on the keyboard. He typed a bullet point about supply chain logistics. The bullet point was flawless.

“I just think it’s actually really sweet? Like, you clearly love your wife. That’s the vibe people are getting. The overall vibe is positive.”

“Thank you for the vibe report, Terrence.”

Terrence hovered for another moment, then drifted away, still holding the whiteboard marker like a trophy. Dave watched him go and thought about walking to the third floor and erasing whatever was up there. He thought about it for about four seconds. Then he pulled the slide deck back toward him and kept working, because the alternative was standing in front of a whiteboard with an eraser while people watched, and he’d already been enough of a spectacle for one morning.

11:14 a.m. Six slides done. His phone buzzed — a text from Lisa. He braced himself and looked.

‘Megan says it’s gone to people outside the company. Someone forwarded it to a contact at Corbin & Associates.’

Dave read it twice. Corbin & Associates. Their direct competitor. He set the phone face-down on the desk and stared at his churn reduction projections, which now felt like a document being prepared for an audience that had already seen him naked.

He picked the phone back up.

‘How do you know that’

‘Megan knows someone there. They sent it to her to confirm it was real. She confirmed it was real, Dave. She confirmed it.’

The period at the end of each sentence. No question marks. No exclamation points. Lisa at her most precise, which was Lisa at her most furious.

“Marco.”

Marco’s head appeared over the partition instantly, as if spring-loaded.

“Yeah.”

“It’s at Corbin.”

The grin didn’t widen. It froze. For the first time all morning, Marco’s face did something that wasn’t comedy.

“Corbin & Associates Corbin?”

“Someone forwarded it.”

Marco was quiet for three full seconds, which was a personal record.

“Okay. That’s — okay. That’s different. Do you know who forwarded it?”

“No.”

“Does Janet know?”

“I’m sitting here trying to finish her deck. I have forty-six minutes. I can’t — I can’t do Janet right now.”

Marco looked at him. The thing underneath Marco — the thing that made him Dave’s actual friend and not just a cubicle neighbor who enjoyed catastrophe — surfaced briefly.

“Finish the deck. I’ll find out who forwarded it.”

Marco disappeared behind the partition. Dave heard his chair roll, heard typing. He turned back to his own screen, where a slide about customer lifetime value projections waited for him with the blank patience of something that didn’t care about his life.

He typed. He built charts. He aligned text boxes with the grid and adjusted fonts and double-checked the Pinnacle Foods logo placement on the title slide. At 11:47 he realized he’d been holding his breath through the entire risk assessment section, and he let it out, and it shook.

11:51. Nine minutes. The deck was twenty-two slides. The last one was a summary page with three key takeaways, and he wrote them in clean, confident language about partnership value and long-term growth alignment, and each word cost him something he couldn’t name.

At 11:58, he saved the file and emailed it to Janet. Just the file. No message in the body. He’d been told not to send emails, but the deck had to go somehow, and he figured a .pptx attachment with no text was as close to silence as Outlook allowed.

He sat back. The chair creaked. From the kitchen down the hall, someone laughed — not at him, maybe, or maybe at him. From Marco’s side of the partition, the sound of a phone call conducted in murmurs. Somewhere outside this building, people at Corbin & Associates had read words he’d written for Lisa in the specific privacy of a marriage, words about her neck and her laugh and what Saturday might look like if the kids went to bed on time. Those words were loose now, untethered from the context that made them love instead of spectacle.

His phone buzzed. Lisa again.

‘Are you going to be okay for the meeting.’

No question mark. But she was asking. Under the precision, under the fury and the Megan Driscoll humiliation and the school parking lot — she was asking.

He typed back: ‘I’ll be okay.’

He wasn’t sure that was true. But the deck was done, and the meeting was in two hours, and somewhere in this building Janet was opening his file and deciding whether the man who’d emailed his love life to the entire company could still be trusted to sit in a room with clients and talk about churn reduction like a professional.

Dave closed his laptop. Then he opened it again, because closing it felt like giving up and he wasn’t there yet. He pulled up the Pinnacle Foods website and started reading their latest press release, because preparation was the only armor he had left, and in two hours he was going to walk into that conference room and be the most competent person in it or die trying.

***

Dave didn’t go to the stairwell. He walked past it, past the kitchen where someone had written something on a whiteboard he refused to look at, and into the copy room at the end of the hall. It smelled like toner and warm paper. The Xerox machine hummed in standby. No glass walls. No glass anything. Just cinderblock and a door that closed.

He pressed his back against the door, pulled out his phone, and called Lisa.

It rang four times. He was composing the voicemail in his head — something short, something that didn’t sound like begging — when she picked up.

“I have nine minutes before I need to be at the dentist.”

Not ‘hello.’ Not ‘are you okay.’ A boundary, drawn with a ruler.

“I finished the deck. It’s done. Janet has it.”

“Good.”

Silence. Not the comfortable kind — the kind that dared him to fill it.

“Lisa, I’m sorry. I know that doesn’t — I’m just. I’m sorry it happened to you. The Megan thing. The screenshot. All of it.”

“The Megan thing.”

“I have to see Megan Driscoll at pickup today, Dave. Three fifteen. And then at the fall fundraiser. And then at every school thing for the next six years. And she has read, word for word, what you want to do with the —”

She stopped. The sentence just ended.

“I know.”

“Do you. Because I don’t think you’ve had time to think about what it’s like on this end. You’re in your building having your HR meeting and your crisis. I’m in a parking lot with a screenshot on my phone that I can’t unsee, from a woman I barely know, who now knows what my husband —”

She stopped again.

“Lisa —”

“What you wrote about how I tilt my head back when I laugh.”

Dave’s eyes closed. His free hand found the edge of the copy machine and gripped it.

“Megan Driscoll read that. About my neck. About what you — and she sent it to me with a laughing emoji, Dave. A laughing emoji and ‘OMG is this real.’”

He could hear her breathing. Controlled. Methodical. Lisa at the dentist in nine minutes, Lisa who had dropped off their children and smiled at teachers and then sat in her car and read the most private thing her husband had ever written about her body, forwarded by an acquaintance with a laughing emoji.

“The stuff in the email — I meant it. That’s the stupid part. It wasn’t a bit. You sent me that casserole text and I was just sitting here eating a granola bar and I was thinking about you. That’s all it was.”

“I know you meant it.”

“That’s what makes it worse. If it was a joke I could laugh it off. But you wrote ‘I still can’t believe I get to come home to you’ and now the whole company knows you feel that way and I can’t even —”

Her voice caught. Just barely. A half-second fracture in the precision, and then it sealed back over.

“I have to go. I’m going to be late.”

“Are we okay.”

Four seconds. The Xerox machine cycled in its sleep, a small mechanical exhale.

“We’re okay. The email is not okay. Megan Driscoll having a screenshot of our private life is not okay. But we’re okay.”

Dave pressed his forehead against the cool plastic housing of the copier. Something behind his ribs unlocked.

“I sent you a link. It’s a casserole recipe. Don’t reply all.”

She hung up. Dave stood in the copy room holding his phone, breathing toner, and for about ten seconds he didn’t move. Then he checked the link. It was a real recipe. Sweet potato casserole, six ingredients, ‘perfect for weeknight dinners.’ She’d sent it at 12:04, while he was still talking. Lisa, who could hold a grudge with surgical precision, sending him a casserole recipe in the middle of the worst day of his marriage. It was either an olive branch or the most elaborate setup for a future joke at his expense. Knowing Lisa, it was both.

He opened the door and almost walked into Marco, who was leaning against the opposite wall with his arms crossed and no grin on his face.

“Found your leak. Greg Hadley in Sales had an auto-forward rule set up — everything from the retention list went straight to his personal Gmail. His wife works at Corbin. It wasn’t malicious. Just stupid infrastructure.”

“Greg Hadley.”

“He’s mortified. He didn’t even read it himself until Corbin people started texting him about it. He wants to talk to you.”

“I don’t want to talk to Greg Hadley.”

“Fair. I told Janet about the auto-forward. She needs to know before Pinnacle.”

Dave looked at him. Marco without the grin was a different person — sharper, more competent, the version of himself he usually buried under comedy because it was easier.

“Thank you.”

“Don’t get sentimental on me, sugar bear.”

The grin came back, but only halfway — a real smile underneath the performance. Dave almost laughed. It came out as a short breath through his nose, and Marco’s grin widened, and then they were walking back toward the open floor together.

Dave’s phone buzzed. Calendar: ‘Pinnacle Foods — Conf Room B — 2:00 PM.’ An hour and forty-five minutes. Somewhere in that conference room, Janet would present his slides to clients who may or may not have heard about the email that escaped to Corbin. He would sit in that room and talk about churn reduction and customer lifetime value and he would do it well, because the deck was clean and the numbers were right and that was the only thing left today that he could control.

He sat down at his desk. The screensaver had kicked in again. He touched the mouse and his slides reappeared — bar charts, projections, the Pinnacle Foods logo crisp on the title page. Professional. Airtight. Built by a man who’d been falling apart and had done it anyway. He opened Lisa’s casserole link in a second tab and left it there, next to the deck, because he wanted to look at something she’d sent him on purpose.

***

At 1:47 PM, Dave walked into Conference Room B carrying his laptop and a water bottle and thirteen hours’ worth of adrenaline that had nowhere left to go. The room was empty. The projector was on, throwing a blue standby screen onto the far wall. Thirteen minutes early. He’d wanted that — wanted to be the first one in, already set up, already mid-sentence in his own competence by the time anyone arrived.

He plugged in. The title slide appeared on the wall. Pinnacle Foods logo, date, ‘Q3 Retention Strategy — Partnership Review.’ He clicked through all twenty-two slides once, fast, checking for typos, broken formatting, anything that might betray the conditions under which they’d been built. They were clean.

Janet came in at 1:53. She carried a legal pad and a pen and moved with the economy of someone who had already decided how this was going to go. She looked at the projection, then at Dave.

“Greg Hadley’s auto-forward has been disabled. IT confirmed. Marco told me the rest.”

“Okay.”

“The Corbin issue stays internal until I decide otherwise. Your job right now is this room and these slides. Can you do that.”

“Yes.”

She held his gaze for one more second, then sat down and opened her legal pad. That was it. No reassurance, no warning. Just the expectation that he would perform, which was, in its way, the most generous thing anyone had offered him all day.

The Pinnacle team arrived at 2:01 — three people, handshakes, business cards, the ritual small talk about parking and weather. Dave shook hands and smiled and said their names back to them and none of them looked at him like they knew. They didn’t know. They were from outside the blast radius, and for the next ninety minutes he could be a person whose only story was churn reduction.

He presented. He stood at the front of the room and talked about retention curves and customer lifetime value and competitive positioning in the Northeast corridor, and his voice didn’t shake. Slide nine had a bar chart he’d built while Terrence told him about the whiteboard. Slide fourteen had projections he’d formatted while Lisa’s texts arrived like small detonations. Slide nineteen had a risk mitigation framework he’d written while holding his breath. None of that showed. The slides said what they said, and he said what the slides said, and the Pinnacle team nodded and took notes and asked questions he could answer.

At 3:12, the clients left. Handshakes again, talk of next steps, Janet walking them to the elevator with her legal pad tucked under one arm. Dave stood alone in the conference room. The projector still hummed. His summary slide glowed on the wall — three bullet points about partnership value, clean and bright and utterly indifferent to the day that had produced them.

Janet came back. She stood in the doorway.

“Good deck.”

She left. Dave unplugged his laptop and closed it and stood there for a moment in the empty room, listening to the projector fan spin down.

He walked out. The hallway was quieter now — the post-meeting lull of a Wednesday afternoon tilting toward four o’clock. A few people glanced up as he passed. A woman from Finance whose name he didn’t know gave him a small, complicated smile. He kept walking.

Marco was at his desk, feet up, phone in hand. When Dave sat down in his own chair, Marco didn’t look over the partition. He just spoke.

“Terrence erased the whiteboard, by the way. Somebody told him to read the room. I think it was Terrence who told Terrence.”

“Good.”

“Also, Brenda in Accounting stopped crying. She says she’s happy for you and Lisa. She said that with her whole chest, in the kitchen, to no one in particular.”

Dave exhaled something that was almost a laugh.

“And the Slack channel got archived. Forty-seven members at peak. You should be flattered.”

“I’m not.”

“You did good in there. The meeting. Janet said ‘good deck,’ which from Janet is basically a standing ovation.”

“Thanks for the Hadley thing. For telling Janet.”

Marco’s hand appeared over the partition holding a fun-size Snickers bar. Dave took it. The hand withdrew. That was the whole conversation.

At 4:30, Dave logged off. He gathered his things — laptop, charger, the granola bar wrapper he finally threw away, the lukewarm coffee from Terrence that he’d never drunk. He stood up and looked at his cubicle, which looked exactly the way it had looked at 8:45 that morning, before everything. Same coffee ring. Same monitor. Same view of Marco’s partition.

He walked to the elevator. Pressed the button. Waited. A guy from the second floor joined him — someone he recognized but couldn’t name — and they stood in the particular silence of two men waiting for a metal box, and the guy said nothing, and Dave said nothing, and the doors opened and they rode down together without a word. Maybe the guy knew. Maybe he didn’t. Dave found he couldn’t tell the difference anymore, and that this was its own kind of freedom.

The parking lot was half-empty in the late afternoon light. Dave walked to his car, a silver Camry with a car seat in the back and a petrified French fry wedged in the center console. He sat behind the wheel and did not start the engine.

He pulled out his phone. One new text from Lisa, sent at 3:47 PM:

‘The recipe has 340 reviews. One of them says my husband loved this.’

He stared at it. He read it again. A woman who’d spent the day fielding screenshots and swallowing humiliation at school pickup, who’d told him in precise, periodless sentences exactly how badly he’d failed her — that woman had kept reading a casserole recipe long enough to find a stranger’s five-star review and send it to him because she knew it would make him laugh.

Dave started the car. He pulled out of the lot and turned left toward home, where Lisa would be and the kids would be loud and dinner would need to happen, and somewhere in the kitchen there was a counter he would never look at the same way again — not because of what he’d written, but because 217 people had read it and the only review that mattered had come in at 3:47 from a woman who loved him in periods instead of question marks.

He drove. The recipe was still open on his phone. Six ingredients. Perfect for weeknight dinners. He was going to make it tonight.